A city’s development is inextricably linked to mobility—the movement of people and goods. Urban planning in the 20th century was based on the separation of dirty, noisy traffic from the unpolluted, human urban fabric, but global megalopolises today still suffer from the growing implications of traffic. The combination of zero-emission, low-noise mobility with deep digitization and AI will have an enormous impact on the evolution of cities and rural areas, while new mobility concepts are expected to change our understanding of communal spaces and infrastructure.How can we rethink the mental and physical relationships between the rural and the urban? How will new mobility concepts shape our behavior? How are city planning, architecture and design going to be affected by innovations in mobility? On a societal level, there is much more to these questions, given that physical mobility is connected with social mobility. Movement has always been crucial to GRAFT’s spatial configurations and their conception of space, derived from their scenographic understanding of architecture. GRAFT spoke to longtime collaborator Stefan Liske about the implications of progress in mobility and its future milestones.

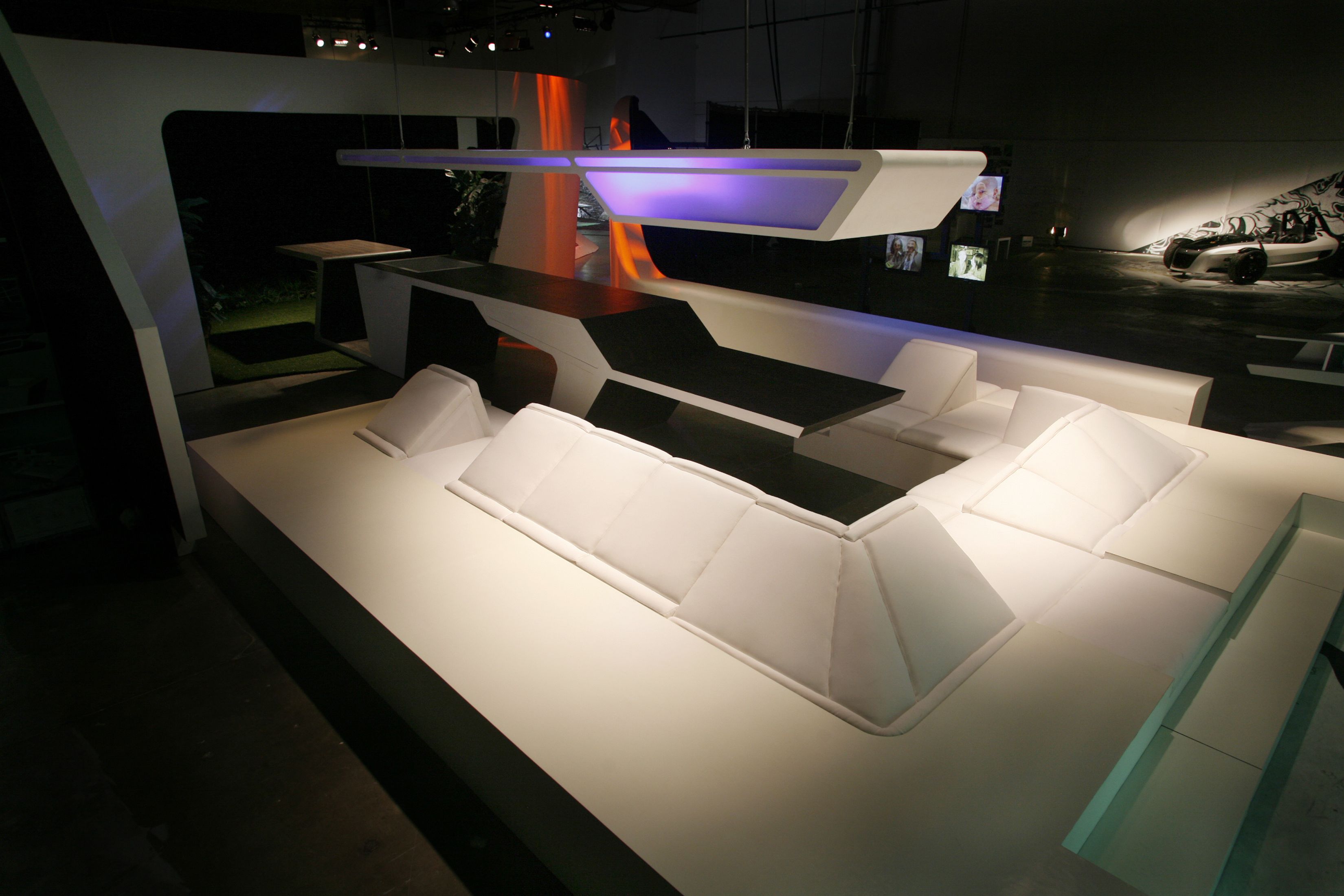

GRAFT: Stefan Liske, our shared history dates back to the time we were setting up our office in Los Angeles. We worked together on the “Moonraker” project for the Volkswagen Group of America, which was about turning societal paradigm shifts and future living scenarios into a tangible spatial experience using built “Life Settings.” The fundamental question for these architectural simulations, which were aimed at different user groups, was: how do you recognize the future? This is a question that’s increasingly being asked by the research departments of the major global manufacturers regarding the subject of regional and urban mobility—but in much greater depth and with different parameters. Ever since electric motors offered the promise of zero-emission mobility in our urban centers, a rise in intermodality caused focus to be shifted to transfer hubs, and the potential of autonomous driving pointed to a more effective and efficient use of space, the crossover points between real estate and mobility have become much clearer. It’s no coincidence that we as an office are now working on more and more projects in the field of mobility, ranging from the branded spaces of traditional automobile companies and service providers to numerous new players in the fields of robo-fleets, drones and maglev systems. According to your expert opinion, which utopia will establish itself in the field of mobility: carsharing and intermodality, a maximum expansion of public transport infrastructures or the complete relinquishment of individual control in favor of autonomous vehicles?

Stefan Liske: I don’t think electromobility will be the great savior. This is due in part to the unclear status regarding the recycling of batteries; another reason is that we might be on the brink of a breakthrough in the field of fusion technology, so a step closer to energy abundance. We definitely need to consider entirely new energy scenarios, ones that the major manufacturers are unfortunately reluctant to entertain. Another utopia that probably won’t materialize is the idea of a completely autonomous, driverless world before 2030. This is unlikely to happen as mobility still signifies personal freedom to many people. On top of this, there’s also the fact that most people want to remain masters of their own routines and continue to define their own rhythms and rituals as much as they can.

GRAFT: The concept of freedom in mobility is something that is currently being renegotiated in the political realm. Studying internationally, having the opportunity to travel, founding an office in Los Angeles, Berlin, then Beijing, being exposed to many different cultures and approaches to architecture—all these things have had a formative effect on our thinking and our commitment to diversity, tolerance and heterogeneity, also in terms of form and style. Today, some people want to collectivize mobility and arrange it in large, communal schemes, partly in order to help combat climate change; others, however, say that long-distance individual mobility was only first made possible to the masses with invention of the automobile, and that being able to drive on their own in a self-determined manner is a real achievement of civilization. Anyway, we are fans of all kinds of transport: collective or individual, surface, air or underground. Do you think that this diversity will decline in the future? A central aspect in the conflict also seems to be the question of how many restrictive rules can survive the democratic process in the long term. Especially when right-wing parliamentary groups such as the Alternative for Germany campaign against such rules.

Stefan Liske: I stand on the side of science. And that means that we should be more strictly regulated, more than we can actually imagine—and not only in the field of mobility. Both the EU mobility commission and the Berlin Senate have had initial discussions about introducing quotas for households regarding CO2, water, waste and consumption. Such quotas wouldn’t just affect which medium of transport you use on a daily basis, they would also affect your choice of vacation, the food you eat, how much your order online, etc. Standardized scientific models increasingly show that we’ll no longer have a chance if we continue to insist on playing the freedom-of-choice card and allow everyone to do what they want. We might need to consider regulating how much we consume and how much waste we produce, at least to a level that’s compatible with democratic values.

Still, we shouldn’t undervalue having a range of mobility concepts. There will always be people who want the rugged performance of a gasoline engine, which is why I think that companies like BMW, Porsche, Mercedes, etc., who aren’t investing everything in electromobility, will keep doing well. Companies like Toyota will continue to produce fuel cells and other, newer types of engine, even though their profits haven’t been that healthy due to the costs of hydrogen production and other technical challenges. In the short term, I think that biofuels such as natural gas are very promising, while fusion technology—which recreates the plasma-based energy production principle found in the sun in small fusion reactors—has the most potential in the long term. These reactors could be produced in a range of different sizes, so even for in-car use, but we’re probably talking more like 2050 for that.

GRAFT: So, electricity would again be the energy source used in these vehicles?

Stefan Liske: Yes, exactly. But when it comes to electricity, there is still the problem of storage. Lithium-ion batteries aren’t a very sustainable solution. The battery technology roadmaps that the big OEMs currently use as a basis will soon be unviable. But things will look better in the next ten or 15 years if oxygen-based storage becomes possible.

GRAFT: We are trained engineers, but we’re also dreamers. We’re interested in using social and technological innovation as a basis for rethinking things, also in terms of urban planning and architecture. You said there would be a number of diverse phenomena and technologies existing at the same time, i.e. different propulsion technologies and multiple modes of mobility: high-speed travel, hyperloop, even new types of air-based transport for goods and people. After a first phase around the turn of the 20th century, when overhead railways and subways enabled intersection-free transport, the use of the third dimension of urban space is becoming a widespread phenomenon again. Elevated maglev railways and drones are now starting to take advantage of vertical space, offering new opportunities for traffic systems in our hopelessly overburdened, ever-expanding metropolises. And when infrastructure doesn’t keep pace with urban growth, it results in undesirable developments, such as improvised neighborhoods, slums or unending traffic jams—the opposite of efficient urban density.

Self-driving concepts, in particular, could have a long-lasting effect on our approach to urban planning. Together with intelligent parking systems, autonomous vehicles will be able to free up space that could subsequently be used by the urban community. For some cities, as traffic increases, this will become a question of survival; for others it will be about negotiating what can be done with this overall gain in spatial provision. It’s a bit like valet parking, but instead we’ll be dropped off at our door, hand over the key to the autonomous vehicle to park itself, which will then pick us up again as needed. This will save on the space required for parking. The more prepared we will be to make our own car available to the community, or to give it over to carsharing schemes, the fewer vehicles there will be in a given urban space. This is one of the most exciting challenges for the future: achieving a good balance of mobility and high-quality urban spaces.

At any rate, many of the dogmas established in the 20th century will gradually fall away. If traffic becomes zero-emission in terms of exhaust fumes and noise, and becomes safer due to the application of artificial intelligence, many of the basic conditions of the Athens Charter—which advocated the separation of transportation routes and urban spaces and which formed the basis of urban planning laws across the world—will no longer be applicable. This would mean that many questions would need to be addressed again, right down to the noise reduction standards demanded of building façades. City planning processes could then approach transportation and urban space in a much more integrated fashion.

At the same time, cars have become modern, small-scale manifestations of third places. What about that aspect? What happens in my car when I no longer want or need to drive it myself? This opens up a huge range of new discussions. In 2016, together with other partners, GRAFT and PCH Innovations carried out a feasibility study on the future use of Berlin’s Tegel airport (p. XX) and the development of an entire urban quarter. At the time, you predicted that autonomous vehicles would be funded by advertising revenues and in this way be free of charge for the end-user. Such a modified mobility model would provide a considerable boost towards the transformation of our urban societies.

Stefan Liske: In the field of mobility, vehicles will soon be able to anticipate our behavior better. Just like our smartphones, background applications and AI companions will react to our demands faster, more specifically and more intuitively—this will be particularly noticeable in the areas of in-car work and entertainment. I think the latter will prove to be a better source of revenue than in-vehicle office or retail services. The vehicles of the future will be functional mobile spaces that will accommodate services such as kindergartens, doctor’s practices or retail outlets. A concrete example of this: a European automobile company recently sold 200 self-driving “robotaxis” to a Californian coffeehouse chain to be employed as “rolling coffee shops.”

I am convinced that the urban environment will profit massively from these developments. We expect to see huge reductions in noise, congestion and the number of accidents on our streets, which will lead to radical improvements in our experience of urban space and thus hopefully in our quality of life. And this is the main reason why autonomous vehicles will be introduced. It is, after all, predominantly about saving lives, not just convenience. On top of this, the cost of transport will go down by around 20 to 30% as drivers’ salaries will no longer need to be factored in—which in turn can be repeatedly monetarized using the aforementioned business models. As of January 2020, in China there are 438 mobility start-ups waiting in the wings. These new players, however, aren’t wasting time with service apps, they are primarily developing autonomous mobility concepts.

Predictions regarding app-based mobility services offered by German automobile companies, which they estimated would make up between 15 and 25% of their future revenues around six years ago, have now proved to be somewhat erroneous. In 2020, of the Volkswagen Group’s predicted 220 billion dollars revenue, less than a billion will be generated by its mobility services. The turning point that we were all waiting for regarding the monetarization of services never happened. When I look out of my window onto the street today, not much has changed—everything looks pretty much the same as it did 15 years ago. It has sadly become apparent in the last few years that the established names in the automobile industry still aren’t really interested in bringing new, exciting forms of mobility and innovative functions onto our streets. Some of the newer players, who are currently trying to shake up the market, are set to score points in these areas.

GRAFT: We want to see this new aesthetic on our streets as well as in our homes, and we are constantly on the lookout for new phenotypes—for example those influenced by the need to rethink the future in terms of climate questions—that enable new forms of social behavior that future mobility concepts can be based on.

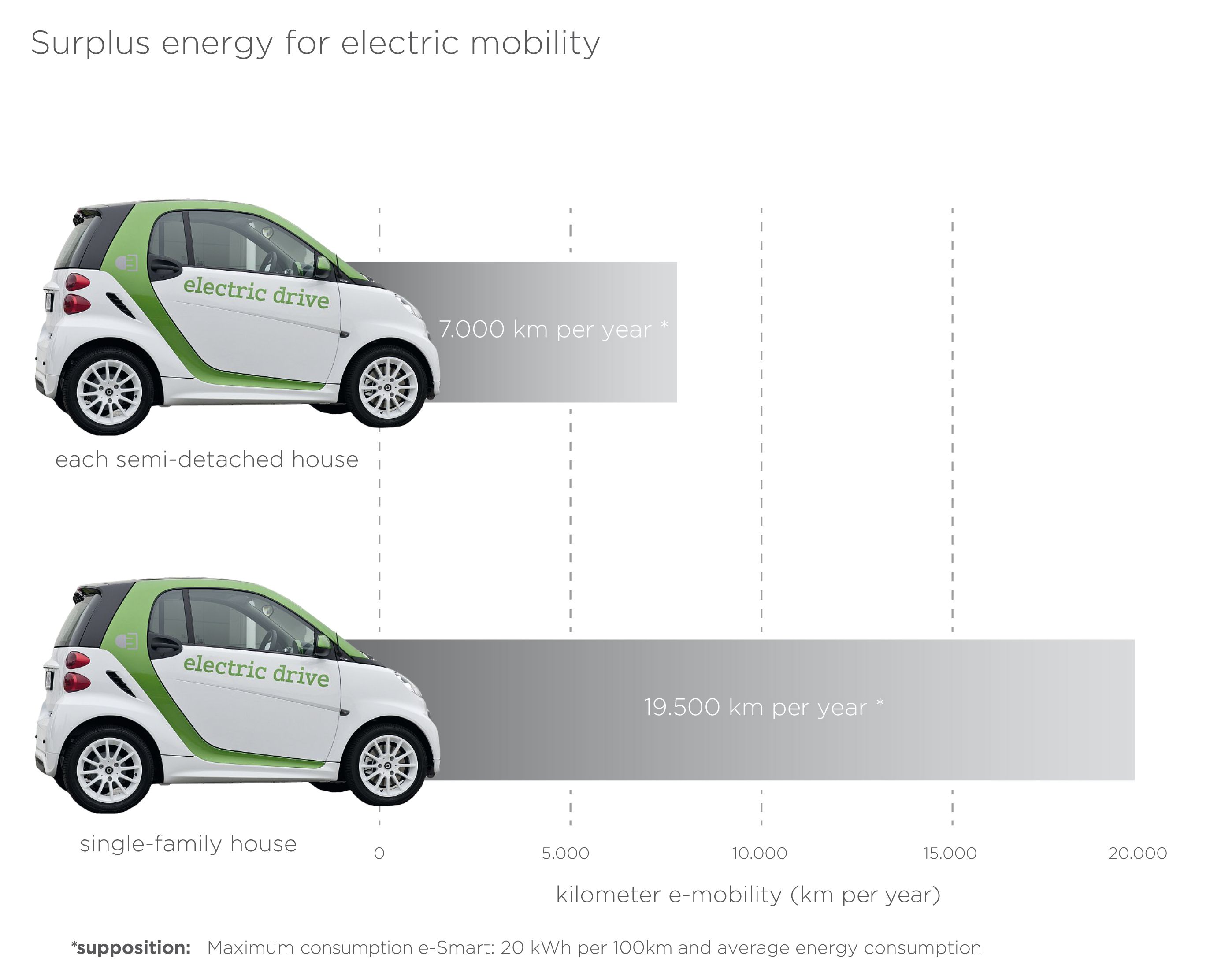

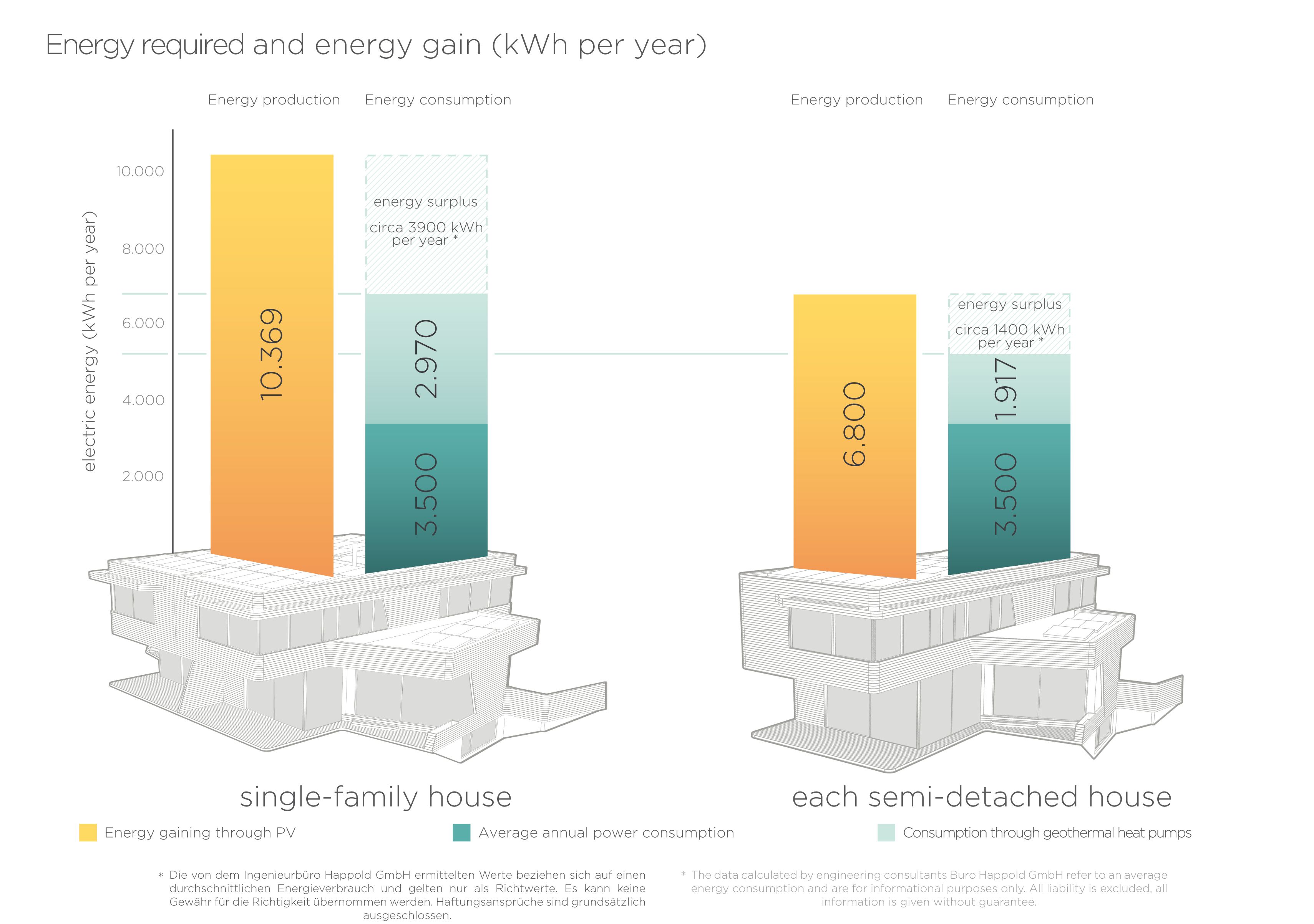

Since we first proposed building concepts whose rental price included electric vehicles that could be charged using the positive energy balance of the houses themselves, we have seen that the touch points between property and mobility have become more evident and the boundaries of the different areas of planning more flexible. Mobility concepts are now becoming the building blocks for co-working or co-living concepts. We can now imagine having clean, quiet, zero-emission vehicles in the same spaces that we work or sleep in. On top of this, there is also the aesthetic question regarding these vehicles and the space they operate in. Nowadays, a functional space for mobility can also be high-quality environment for personal interaction—there is a more discerning aesthetic expectation relating to these spaces. Our office addresses precisely these topics, and with this book we are trying to ask questions regarding future identities and their aesthetics on a number of different scales—from charging stations and interior branding to houses, blocks and entire cities.

There have always been correlations between the aesthetics of the automobile industry and architectural innovations. For Le Corbusier, the entire formal language of classical modernism was inspired by the automobile and shipbuilding industries. In actual fact, the rounded corners of early modernism were justified by the simple necessity of providing a faster, safer way to take of corners. The opulent car designs present for many years in the United States were a manifestation of the country’s faith in its future direction. Besides function, the emphasis was very much on beauty. Individualized mobility and motorized delivery led to the rounded buildings found in the early phase of modernist architecture. Horizontal window bands that suggest horizontal movement, building silhouettes that seem to defy gravity, these things lent architecture an air of dynamism after centuries of tectonic verticality. Sometimes when you encounter modernist architecture, there is a palpable sense of the exhilaration for new technology and mobility and an optimism in creating the structures of the future. Today you can see there is growing demand for architectural quality in the field of mobility. This is expressed in the architectural projects we have realized for automobile companies like Volkswagen and Mercedes, the e-charging stations we created for E.ON, the VoloPort stations we developed for Volocopter air taxis and the design for Max Bögl’s maglev system. And that is related to clean energy and a fascination with new forms of mobility. We hope that our commitment to a society in transition, with its new indicators, objectives and associated innovations, will be reflected in the provision of higher-quality architecture and spaces that are more tailored towards the needs of people.

Stefan Liske: That’s my hope, too. But to achieve this, beauty has to become valued as quality once again. Apart from some classic cars and a few sports cars, they aren’t many models that can be considered beautiful—in the truest sense of the word—in the automobile industry at the moment. Cars that really elicit a “Wow!” like furniture, watches, art or architecture might. Some of the newer players plan to deliver vehicles in the future that boast completely new material or functional concepts. I predict that Chinese manufacturers in particular will soon overtake European and American companies in the delivery vehicle sector, because production costs alone are 20 to 30% lower. These manufacturers now have all the means necessary to finally express their cultural identity by applying their unique formal language, materials and country-specific functional concepts. The Chinese market is currently in the extremely exciting identity-establishment phase, which will be followed by the identity-expression phase. In Europe, on the other hand, we are in the midst of a huge wave of job losses and are witnessing how the historically nurtured loyalties between automobile companies and consumers are being gradually eroded by environmental scandals, crude lobbying and meaningless lip service.

I could easily imagine that the market shares that European and American companies will lose will shift to Africa. It’s currently home to around 800 million people under the age of 30, many of whom want to work and realize their potential and are urgently seeking access to higher living standards, prosperity and free enterprise. Besides energy, water and food, mobility is a fundamental building block for achieving this, but viewed differently to how we know it. And this “thinking differently” is something that the established manufacturers will struggle with once again.

GRAFT: After our experience with the SOLARKIOSK (p. XX), I’d agree with you one hundred percent—everything starts with the provision of energy. The food supply, too, can only be guaranteed if the energy question is resolved. So much food is left to rot in the field because the mobility concepts aren’t available to get the food to the places it’s needed. The energy supply system in Africa needs to be expanded in a decentralized way: if one were to scale up the SOLARKIOSK system, which currently only produces a small amount of energy using photovoltaics, then things could get really interesting. Regarding mobility, we are really focusing on the issue of last mile distribution. There’s going to be a big breakthrough. As a continent, Africa has already seen large-scale success with its telephone network. Mobile payment is another effective model that grew from the necessity of decentralization. Maybe mobility will be the next big leap forward. It’s interesting that we initially developed the SOLARKIOSK because we wanted to provide energy to rural areas, and we’re now modifying them to serve as charging stations for drones and e-bikes. These small kiosks have turned into mobility recharging hubs. Such new, decentralized systems create exciting and profitable business cases that could eventually be exported to Europe and the Western world. Over the next few decades, Africa will surely teach us a lot about connected yet decentralized energy supply models based on small, autonomous hubs. And this might be the only way we’ll be able to do things in the future.

Stefan Liske: Exactly. What’s one of the central economic principles in Africa? Barter and exchange. There are a lot of Western economists today, like Thomas Piketty and Paul Mason, who are developing new, postcapitalist logics. They predict that alongside decentralized, digitized cash flow, bartering and exchange models and other microfinancing systems will become more established in the Western world in the next 15 to 20 years. In the future, the economy will become more community-based, especially in urban centers. To achieve this, though, we will need to establish a new sense of community with new value systems and the corresponding platforms for interaction, exchange, trade, etc.—millennia-old mechanisms and values that have been lost through the process of technological development.

GRAFT: Are we talking about ideological tribes here? Does the past still work as a model? Will private transport increase or decrease? This is where artificial intelligence and the autonomy of mobility overlap. In the 1990s, Rem Koolhaas created a European map that depicted the continent in terms of travel time, using distance, speed and accessibility. Today we expect trains to offer an alternative to short-haul flights. Companies like Max Bögl are bringing transport systems onto the market which, based on a similar capacity to a subway, would cost a third of the price and could be built in a third of the time—and, by offering intersection-free urban mobility, would be far superior to any tram. Even the introduction of drone technology as a form of passenger transport is becoming increasingly likely. If we approached it properly, there could be such a high level of competition in urban transport that technology would advance much faster. This is especially relevant when it comes to regional accessibility and intra-city transportation.

To what extent will the relationship between rural and urban areas change in the future? Even in an urban context, people today talk about the re-emergence of the rural—the yearning for the village and the neighborhood. At the same time, there’s a blurring of the physical and definitional boundaries between the urban and the rural. Connections are becoming more important than boundaries. Cities are changing from destinations into transit areas within a global network of metropolises.

Stefan Liske: There will be an increase in individual passenger transport between urban and rural areas. We are already witnessing the first signs of an urban exodus in Germany. Within 15 years it will be possible to carry out a highly paid, highly qualified, demanding job remotely and not have to go to the office at all. I think this will be accompanied by a development in the niche field of mobile living. There is a growing market for caravans, trailers, mobile homes and tiny houses, illustrating an increased desire to lead an off-grid life—with little to no dependence on resources, the state and large corporations. Which means we will see more and more people attempting to live in a self-sufficient manner, providing for their families and communities using independent water and energy supplies, farms and individual-centered sources of income. In the context of climate-change induced floods, droughts, heatwaves, fires and air pollution, and given the development of intelligent, sustainable off-grid solutions in the fields of water, energy, food, health, etc., this phenomenon takes on a whole new significance.

GRAFT: Do you not think that this urban exodus might be a transitional trend? New mobility promises us that through the application of artificial intelligence and autonomous vehicles, parking spaces will be turned into green spaces and CO2 and noise pollution will be reduced to zero. It’s ultimately a promise that guarantees a huge improvement in the quality of life in urban areas. In our opinion, these phenomena—the desire for the local, the neighborhood within the city, for belonging, both to tribes and the community—are all clear indications of a yearning for a village character within the urban environment. Maybe if this happens, urban exodus will no longer be an issue, and everyone will be rushing to move back to the city again.

Stefan Liske: For many people, these prospective changes to the urban environment have been too long in the making. I also believe that we should really and truly rediscover nature and our rural regions, but without subduing them—it’s about protecting, rewilding and restoring.

GRAFT: Which would mean an enormous increase in mobility. Let’s think about the question of scope and consider distances greater than those between urban and rural areas. At the moment, global travel is a relatively low-threshold activity that is accessible to a large number of people. Not everyone can afford it, but more people than ever before. Now Greta Thunberg is showing us that we should travel to New York by sailboat. From your perspective, are there things in this field that will allow us to maintain this freedom of global movement, perhaps technological advances or innovations that will make flying less harmful for the environment, for example? Or is reduction and renouncement really the order of the day, here?

Stefan Liske: Behavior relating to global mobility will change massively, especially in the younger generation, as they longer want to fly because they are aware of the facts and are deeply concerned about the future. They know that they are facing a mammoth task. I can imagine that an interesting, truly innovative set of solutions will be developed, one that could even capitalize on climate change and create new jobs in the process.

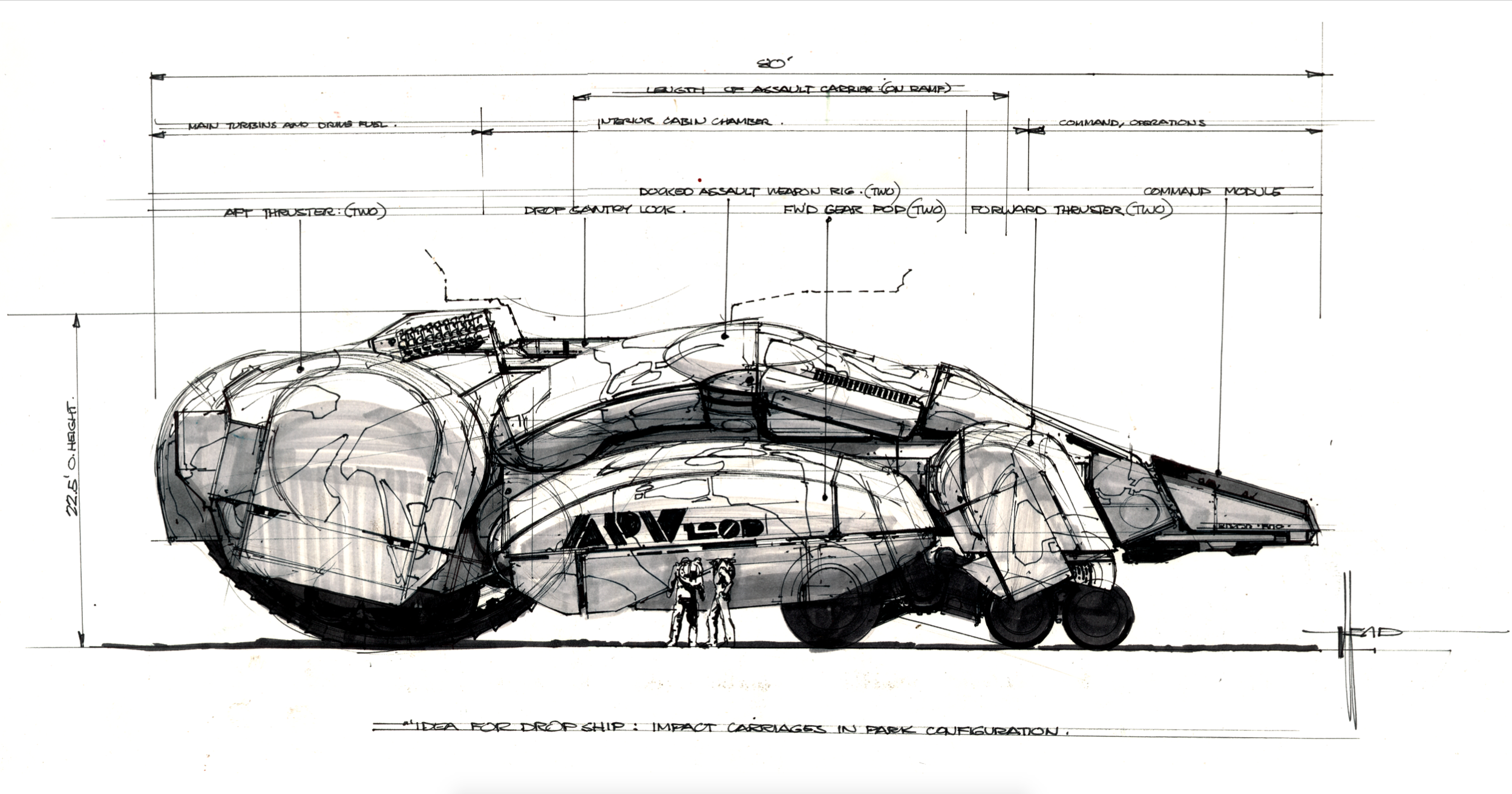

GRAFT: As for the Moonraker project that we collaborated on, some of the predictions we made in the “Sustainability Earth – Green Topography” scenario really hit the nail on the head. The hypotheses regarding the growing interconnection of IT networks and intelligent building control as well as those on fluid, dynamic interiors were quite accurate. Some of the other assumptions, however, became quickly outdated or didn’t prove to be true. If you look at GRAFT’s current projects, for example those for urban air taxi service developer Volocopter (p. X), Max Bögl (p. X), E.ON (p. X) or the roof of the Autostadt, what identity does our visual language convey today? We believe that our success in these competitions shows that the world of new mobility finds its expression in dynamic architectural forms. It could also be down to the fact that our way of designing is very scenographic, conceiving of spatial experiences as a continuum over time. Of course, even in times of great change, it’s also essential to express a certain amount of optimism for the future—albeit with an amount of balance and caution. The starting point for this might sometimes be the future-oriented design language found in the world of sci-fi films, sometimes it might be inspired by organic forms and the language of bionics. We believe that this visual expression will be best suited for creating an awareness that human actions are responsible for changes to the basis of our existence and can no longer be separated from what we have until now understood by the term nature.

Stefan Liske: It might sound controversial, but I believe that the biggest and most significant change that will happen in the next one to two generations will be that of humankind.

On one hand, we live in an age in which we have made inroads into large parts of quantum physics—we can already use quantum computers to efficiently solve complex everyday problems. This might be, for example, traffic flow analyses, AI- and neural-network based analyses that are so complicated that they can only be calculated by a quantum computer.

Looking beyond this, however, the next long-term breakthrough in quantum physics will be in making this phenomenon accessible to everyone. Simply put, quantum logics are logics of energy exchanges between objects and people that have not yet been fully decoded. And I think that as humans, the progressive decryption of these logics will offer us a different relationship to our conceptions of energy and frequency. New, emerging fields of academic research are currently trying to verify and measure forms of energy flow between people. This will lead to a huge increase in the understanding of phenomena that exert control over us as physical beings. The measurability of these phenomena will then be followed by their practical application and the possibility of actually influencing them.

This, as well as all the developments we talked about earlier, won’t just massively influence our behavior, it will also shape our entire sense of aesthetics, our sense of language and our sense of a truly functional, objective aesthetics, i.e. an object-bound aesthetics. I think this realm contains a major source of creative riches, and your curiosity and experience make you the ones predestined to unearth it.