This interview was produced under the conditions surrounding the global Covid-19 pandemic—a time in which many of us were subjected to unprecedented spatial experiences in the public and the private sphere. Our working environments, in particular, underwent drastic changes as a consequence of remote working and a subsequent shift to digital tools.

GRAFT has always been a close observer of transformations in the work sector, whether they originate in the processes of digitization or are rooted in the radical mindsets of new generations renegotiating their priorities between living and working. With many aspects of work becoming increasingly diversified, GRAFT’s office designs experiment with flexible and adaptive spatial models for an evolving range of requirements while respecting the need for resilient solutions. How will these major changes manifest themselves in architecture and interior design? In this dialog with WeWork founder Miguel McKelvey, GRAFT sought to uncover new approaches to work environments and to work itself.

GRAFT: When we visited WeWork in New York, we went to see your WeLive space right next to the East River on Wall Street. The project, a refurbishment of a classic 1960s mid-rise, functions like a city, it’s a really interesting concept of sectioned neighborhoods. Your architecture team explained that the names given to the different areas are terms borrowed from city planning: your users navigate through neighborhoods and communal areas, with staircases becoming connectors and meeting points.

Miguel McKelvey: We were indeed trying to implement a neighborhood that resembled the feeling of our hometowns. As a kid, you knew if your neighbors were home because the doors were open, and you felt—and were—overseen by the community, of which everyone was a part. We thought about putting in screen doors on the apartment floor and seeing how many people would leave their doors open. Unfortunately, this idea didn’t comply with the New York City fire code and we weren’t able to implement it. With WeLive, we experimented with things we’d learned from the work environment. How do these findings translate to a residential setting? How can we actually encourage new behaviors in people? How can we add notions of surprise?

GRAFT: Learning from the re-organization of work through ideas of community and applying it to a completely different typology, for example living, is also of great interest for us. Since it was founded in 1998, GRAFT has planned and realized a large range of hospitality projects. We learned to experiment with ideas from such commissions and apply them to other typologies because, after all, hospitality also concerns living environments—even if they are temporary. As a designer, you can test out a lot of residential scenarios in a hotel. Things that work well in this field, for example how hotel guests organize themselves within a space—both functionally and regarding communal aspects—, are usually introduced in the residential domain a couple of years later.

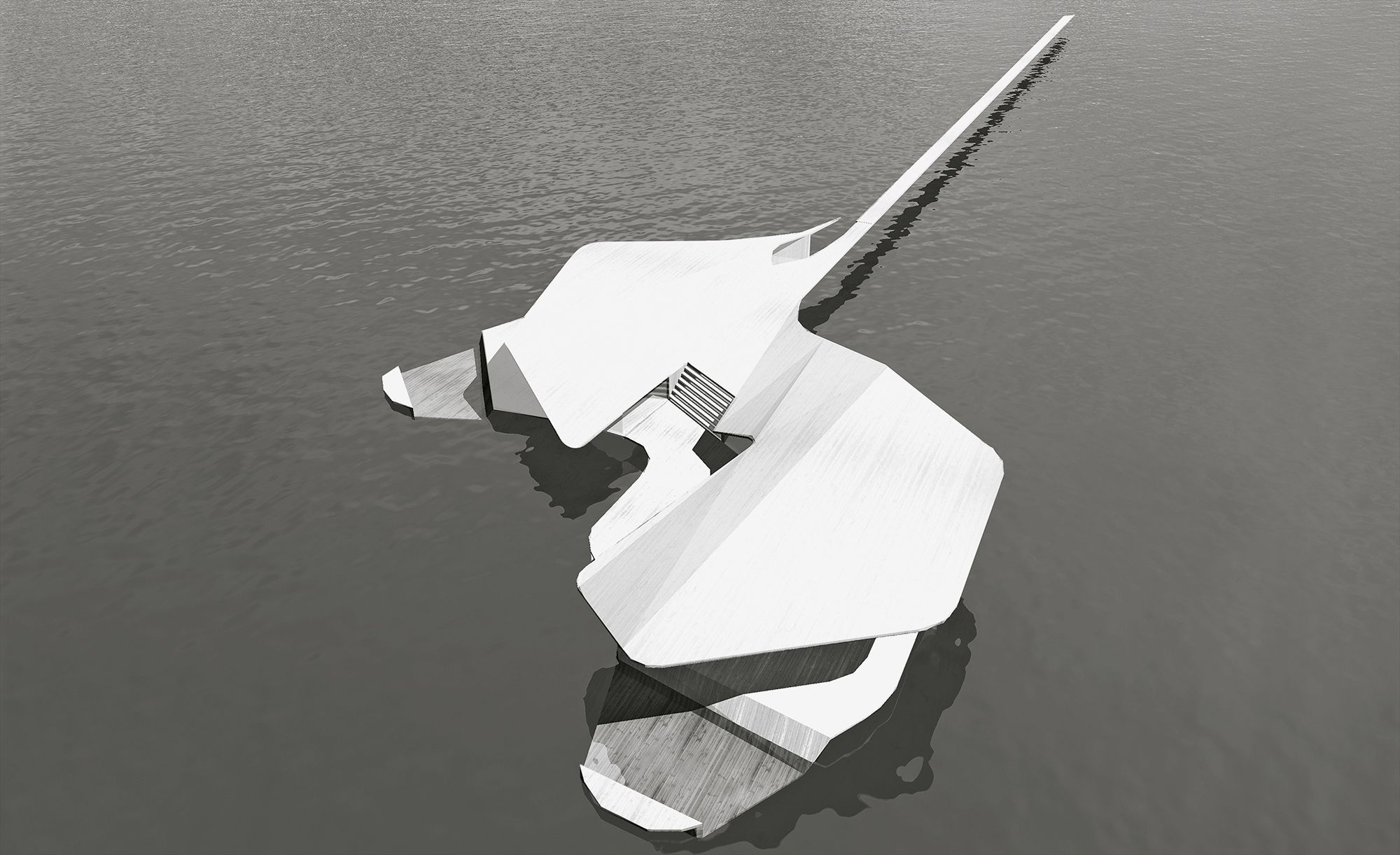

We are currently working on a highly flexible startup cluster. The underlying idea is to avoid defining where users should live or work, because these lines are becoming increasingly blurred anyway. The design is heavily based around the idea of community. People live and work in five wooden towers that are situated on a plinth where all the communal amenities are located: cooking, cleaning and eating are done collectively in these communal areas, positioned around a large, covered marketplace. The cost efficiency gained in concentrating kitchens and washing machines in communal areas is quite interesting. The real efficiency, though, is a social one, as people are smarter, healthier and happier in a dynamic community. We also ran into problems with zoning because German law demands that an area be designated as a place for either living or working. For us, the beauty lies in the hybridization of functions.

Miguel McKelvey: I’m always so perplexed and frustrated why zoning regulations aren’t more adaptable. I’m sure current technology would allow us to compensate for everything.

GRAFT: It seems that it’s not necessarily the regulations per se, but the way they are interpreted and translated. In a bolder, more innovative environment, you can actually experiment a lot within the regulations and really push the envelope. The sad thing is that official authorities usually have working environments that are opposite to this—hence fostering a mindset of always covering your back and creating a silo mentality. If we could change their working cultures regarding the idea of exchange and communal encouragement of innovative thought, our cities might then reflect that. It would be a very interesting task to rethink the workflow and collaboration through space in a city planning department.

But suggestive spatial layouts are just one part of how innovation will challenge our working environments. Technological and demographic changes will cause major shifts in the labor market, with new emerging careers and modes of work. With machines doing more and more predictable and routine tasks for us, the future of work seems to be rooted much more in the notion of “purpose.” How will work be perceived as digitization moves along and we are replaced by robots or algorithms?

Miguel McKelvey: I haven’t really ever gotten to a place where I feel super comfortable proposing or suggesting any conclusions, primarily because it feels so imbalanced what those proposals would mean for different people. When you look at it from a typical perspective, you think about the elimination of jobs that are labor, which aren’t necessarily occupied by knowledge workers. In this case you’re actually talking about a class issue and fair access to our economic system. This issue will not be solved by architecture or design. It’s different when I think about it for the people who might benefit from less work, like myself: What would I do if I only needed to work four hours a day to maintain my lifestyle? It’s a fantasy at this point, but I could follow all these other intellectual pursuits or a healthier lifestyle. For that you could design great spaces to support new purposes, interacting in different constructs of physical and intellectual discourse. Still, there will always be this affordability line that excludes people. So, what do we do about that? You would have to go deeper into racial or class discrimination and other societal aspects, which are also part of the whole story.

GRAFT: We agree. It’s definitely going to raise major questions of social justice. But what if you had to look at it from an idealistic viewpoint? Let’s say that all these inevitable developments would open up multitudes of resources and more people would be able to nurture the uniquely human trait of being creative. If work itself were to become more purpose-driven, in contrast to money-driven, how would that change the working environment? If people specifically went to work to be creative and solve problems, it would allow the emergence of a new aesthetics of physical workspaces that promote the uniquely human skill set of creating meaning through social and emotional intelligence, collaboration and creativity.

Miguel McKelvey: In our construct of WeWork, we have seven or eight different workspace case typologies. For example, we have very small phone booths, which are one of our most popular use cases. I wouldn’t use them personally, except to make a quick call, but some people will go in there for the entire day. They get in early in order to claim it, and they are happy to be in this little box for eight or ten hours straight. You have to acknowledge that there’s a huge diversity in the way people show up in space and what they feel comfortable with.

I think people have a passive relationship with themselves, meaning they don’t actually choose the spaces that are most conducive to their planned activity. We have all these amenities that aren’t used in the “right way.” How do we get people to use this array of amenities that we offer?

In this context we are actively tackling thresholds. It’s similar to the online marketing rule: the more clicks, the less sales. We want to remove the number of steps towards a decision. How do you remove those thresholds and those numbers of clicks in real life to actually get to that activity? That’s a big premise of why we started. We are trying to make our spaces really multifunctional. So, when you walk in one morning, there might be a bootcamp exercise at 8am in the common area. The next day you can just wear your shorts in the morning and join in. Or rather than putting a speaker with an audience in an auditorium, we put a keynote presentation in the foyer, so you have to walk by and can’t avoid it. Maybe you pause, spend an hour and a half there and then there’s a happy hour afterwards, where you meet someone really interesting to discuss the subject with. That’s the ideal case for us. It’s part of the challenge to find out over time what the perfect configuration is, the one that will result in fulfillment. It’s hard for people to break out of old habits.

GRAFT: As architects who derive inspiration from user-centered design thinking, we want to know what the people who inhabit or use our spaces really need and want.

But it seems that working communities and individuals have not yet unlocked their full potential within creative structures and setups.

If we look at the architectural history of workspaces, we notice a reinvention or a trend hypothesis appearing approximately every ten years. Since the turn of the century, for the first time, there seems to have been no homogeneous idea about how the next generation of work will evolve. You are suggesting that working itself, as well as working environments, will become more eclectic and open. The seven use cases you mentioned could probably be broken down into even more variations.

Why are we increasingly becoming migrants between different identities and communities that seek to hop around, even commuting within a workspace? Is the grand experiment that scouts different forms of life and work the new reality or just another trend?

Miguel McKelvey: The first dot-com boom, which was around ’98 or ’99, switched the mindset for a lot of people. It became clear that you didn’t need to follow a certain, well-known path in order to become successful. During that explosion, there was a detachment among young people, who discovered that they didn’t have to wait 20 years to move up the ladder if they just started their own company. At the same time, the companies that became more corporate were responding to that vibe. All these people that were unleashed from the cubicle then needed a lot of new spatial programs and entertainment to engage them.

GRAFT: We were very lucky to be in California at that time. The guys you just mentioned were our first clients when we started GRAFT in 1998. They were younger than us, and we were only 30 ourselves. We designed those dot-com offices. The design brief was often like: “Our employees work nonstop. They basically live here. How do I keep them? How does boy meet girl and vice versa?” Knowing that most employees spent almost all their time at the office, we basically tried to create an environment that embraced both work, leisure and life. That was new. At the same time, the workforce was still expecting cubicles. When we were done, the companies were either so big that they had to move into a bigger building and we had to start all over again, or they had collapsed. When we came to Germany a few years later, nobody had even heard about these developments. No one understood our designs either.

Miguel McKelvey: I think first and foremost people want to do something that they feel is purposeful, and they want to be directly connected to that purpose. Secondly, they actually want to have fun, especially young people, pre-family. Their social network is often where they work. If they move to New York City without knowing anybody, as early employees at the company they’re working for they’ll form friendship groups that they’ll probably have for life. I don’t know how many generations back, but probably before the dot-com boom, their expectation wasn’t to have fun.

GRAFT: We agree. We think they expected that their life would start at the end of the working day. They didn’t envisage that it might be otherwise. The permanent shift of this understanding makes sense, even more for employers. Efficiency and efficacy are not based on squeezing everybody to the core. Fun and health equals productivity—with that formula in mind, everything changes for the better.

In Germany, it is regulated by federal law that certain workspaces have to be equipped with natural light and ventilation. These regulations are based on the simple scientific fact that biological entities require natural light and air. As architects, we always think about how buildings can be made more efficient. What does this mean besides placing zones that don’t require daylight in the center of a building? It’s not something that should only take money into account; it should also consider people’s health and well-being. If you understand that better buildings bring better results, everybody wins because productivity increases.

Miguel McKelvey: As architects, you are in control of your environment. To very few people, very few leaders, does the physical space ever occur to be pivotal. They would easily walk into a horrible conference room that feels super claustrophobic and has ugly furniture and accept it as it is. They don’t question if this is actually the best place for great energy to come from in a meeting. How do you break free from your mental construct and continue to grow and change and evolve? You probably need some input that will inspire you to do so. And where do you spend all your time? In the workplace…

GRAFT: When I look around your WeWork office here in Berlin, I wonder if you were inspired by the Urban Theater. It’s like what you might imagine Florence to look like in the 15th century, when everybody was out on the street.

Miguel McKelvey: I think authenticity really matters, and it flows through when the people who started the business continue to be there and lead it. I was and still am super-interested in this challenge of getting people to be more open to each other. You can look at it from an event perspective and create peak experiences that bind people together. The combination of the physical space and the social programming needs to be really good. Our starting point wasn’t a business model; we came up with an experience and a connection to an energy that we wanted to spread.

GRAFT: A synonym for authenticity might be identity. Talking about identity besides your own, who do you work for? You are providing a home for their career paths. That’s a big responsibility. And given that you host people from many cultural backgrounds across the world, what’s around the corner? What’s next? For us, repetition is the most boring ingredient. We try to design different typologies for different communities on different continents. That’s difficult, but we’re happy when there are challenges and problems we haven’t solved yet. What do you think is the next big challenge in the new workspace?

Miguel McKelvey:

One of the most important challenges is diversity—also in the design of our workspaces. There’s so much complexity from a more human societal perspective. At the moment, we are closely examining our strategy in regard to diversity. Studies show that diverse teams are stronger.

I certainly designed the first WeWork in my own image, meaning my own personal style was the inspiration for it and I made the choices I made within the context that I existed in. Still, I don’t want our spaces to be made by white people for white people. We are actively examining and making steps on how we can make our spaces more inclusive.

We were also looking into large supermarkets in rural areas of the U.S. They are often situated within complex socioeconomic divisions and their employees are facing job losses through automatization. We are asking: what could we do to strengthen these large retail centers as places of learning, of growth, of the future? The aim would be to expose employees and customers alike to their diverse potential. What if you developed these places as reskilling centers that aren’t just about learning low-level technology but about connecting to a much broader set of things?

GRAFT: The rise and fall of the mall was already a big topic when we studied at SCI-Arc in the late ’90s. Such spaces are highly interesting because they are the modernist, somehow aseptic translation of medieval marketplaces. The re-appropriation of real estate and its original spatial program into other hybrids in the transition phase is even more interesting today.

Eventually, due to automatization processes, we won’t need as much office space as we did before—how are we going to transform these spaces then? Is it actually high-quality inner city or not? There is a similar discussion about the former industrial sites that exist all across Europe, a relic of industrialization over a hundred years ago. Among them are many beautiful “cathedrals of labor,” monuments of industrial architecture. Many of these amazing spaces are now being re-used. They’re wonderfully built and are thus of great architectural value. I believe that malls could be of great value too, as they have a different connection to younger people.

Miguel McKelvey: I wonder what would happen if you unleashed young kids and artists on one of these empty malls. What would they do? How would they occupy it? This has actually happened in neighborhoods in New York City, whether it was Soho or Dumbo or even Red Hook. You had these places that were made for manufacturing and then the artists came in, took them over and started producing work there.

GRAFT: There’s a reason why the street-art scene is still so big in Berlin: they had the Wall, the biggest canvas in the world. Sometimes it is exactly these obstacles in a community that foster innovative and disruptive thinking as a rebel response. The Wall was given a completely unforeseen new urban use, it became a place of free communication. When the Wall was finally overcome, the experience not only established a strong part of a global art scene but the true identity of the city of Berlin, the city of freedom. We envisage the emergence of new urban identities once we are liberated from the modern dogma of separating living, working and manufacturing in our urban centers. Before modernism, urban areas worked exactly like this. Imagine the reduction in mobility and energy needed if these functions were to be hybridized again, clustered around temporary communities and neighborhoods that can easily change and regroup. We believe that we are in an extremely interesting moment in time when it comes to reclaiming our cities.

While working on this publication, however, the world has been going through the crisis surrounding the spread of Covid-19. Experts from different fields predict that it will have a profound and lasting effect on the entire world—the workplace included. Deborah Tannen, professor of linguistics at Georgetown University, predicts that the idea of ‘the personal’ will permanently be associated with danger. She says, “Instead of asking, ‘Is there a reason to do this online?,’ we’ll be asking, ‘Is there any good reason to do this in person?’” 1 . Our digital work routines, which used to be an unwelcome alternative to physical encounters, may become the norm. And companies will be better prepared for remote work. This development could potentially lead to a bigger emphasis on tech, such as telecommunication and artificial intelligence vs. travel. The relevance of New Work services lies in the many ways of creating New Work communities and unleashing their social power. This is challenged in times of social distancing. But another important aspect of New Work environments is the facilitation of these working communities via telecommunication, meaning connecting many people smoothly through new augmented and virtual realities, lowering thresholds of digital co-working. Do you see a paradigm shift in the future of New Work environments, as Tannen does? Will the meeting table be more virtual in the future?

Miguel McKelvey: While the world is going through a paradigm shift, I think the effect will be a more purposeful use of space and time. As we all emerge and begin to create the new normal, we will evaluate the cost of our commutes and the associated risks of being surrounded by people. In doing so, we will value our time spent with people even more. We will see our time at the office with co-workers as something no longer to be taken for granted, but rather something to be cherished. We will have more appreciation for the spaces designed for work, because our homes are certainly not conducive to the wide range of use cases we’ve identified. As much as it’s nice to be home, many of us would admit that the static environment can be stifling. For me, I desperately miss the buzz of people moving around space, as well as the random, casual conversations. On top of that, seeing less overall, absorbing less, will reduce openness and empathy, which is certainly essential for our path forward. Those that live in bubbles or closed communities are known to be less open-minded and less interested in diverse thinking. We will need to encourage people to again engage in open, diverse forums and to take risks—with their ideas and their actions.

https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2020/03/19/coronavirus-effect-economy-life-society-analysis-covid-135579